by Brashcandy

Sansa and Sweetrobin depart the Eyrie in A Feast for Crows. ©Anndr

Tourneys in the Song of Ice and Fire saga have never been simple affairs. Whether ostensibly organized to celebrate weddings or birthdays, honour officials in high positions, their noble family members, or some other festive occasion, these tournaments — grand or small — have been sites of intrigue, power struggles, attempted rebellions, romantic entanglements, and political scandals. In every tourney that Martin has turned a sustained gaze upon, we have seen the oft deadly game of thrones in operation, where deceit and trickery hold sway, and personal ambition comes with high costs. Therefore, with Sansa’s TWOW sample chapter revealing another planned tourney that Martin will explore in significant textual detail, we should expect to see many of the same thematic elements and surprising plot developments arising from this event at the Gates of the Moon. This is why, for the purposes of the following analysis, I have found it so instructive to closely examine the five tourneys in the ASOIAF universe that we have been given substantive information on: the Hand’s tourney in A Game of Thrones and Joffrey’s name day tourney in A Clash of Kings; the tourney at Harrenhal in the year of the false spring; and the pair we read of in the Dunk and Egg novellas, staged by Lord Ashford and Lord Butterwell respectively in The Hedge Knight and The Mystery Knight.

Before we get into the central features of the aforementioned tourneys and the revealing parallels that are contained in Sansa’s storyline, let’s spend a little time exploring just why tourneys are such a critical component of Sansa’s arc and development. Rivalled only by her younger brother Bran for her early idealism and valorisation of knighthood, Sansa begins the novel with starry-eyed beliefs that these warriors are fundamentally good and honourable, uphold a chivalric code of conduct, and behave as she puts it like “true knights.” Tourneys, with their grandeur and spectacle, initially dazzle and amaze the young girl we are introduced to in A Game of Thrones:

Sansa rode to the Hand’s tourney with Septa Mordane and Jeyne Poole, in a litter with curtains of yellow silk so fine she could see right through them. They turned the whole world gold. Beyond the city walls, a hundred pavilions had been raised beside the river, and the common folk came out in the thousands to watch the games. The splendor of it all took Sansa’s breath away; the shining armor, the great chargers caparisoned in silver and gold, the shouts of the crowd, the banners snapping in the wind . . . and the knights themselves, the knights most of all.

“It is better than the songs,” she whispered when they found the places that her father had promised her, among the high lords and ladies. Sansa was dressed beautifully that day, in a green gown that brought out the auburn of her hair, and she knew they were looking at her and smiling.

If tourneys are the staging ground for displays of jousting skills by knights, they become an important training ground for the elder Stark daughter, educating her in the violence and dishonourable tactics that can regularly occur, revealing and sharpening her empathetic skillset, and fostering her relationship with Sandor Clegane. Not to be overlooked is Lord Petyr Baelish, aka Littlefinger, who also initiates his connection to Sansa at the Hand’s tourney, transferring his ruthless obsession with Catelyn to her daughter, and begins to look for ways to exploit her naïveté. For all the passivity that appears to define Sansa’s time in captivity with the Lannisters, she plays a pivotal role at the two tourneys she attends, elevating her status from that of mere ornamentation and insignificant hostage.

By opening Sansa’s TWOW chapter with the plans for the imminent staging of a tourney of sixty-four competitors, Martin is confirming to the reader that whatever may develop out of this event with respect to her future prospects, a tourney is familiar territory for Sansa, and one where she has a habit of forming unusual and clandestine alliances. Although she is still in LF’s orbit of influence, Sansa is no longer imprisoned or cut off from potential sources of assistance. She is older and wiser, with considerably more self-confidence and daring, divorced from the childish estimation of knights, and in possession of a strategic understanding of the wants and desires that motivate those around her and how to manipulate such to her favour. It may not be overstating the matter to say that in agreeing to host the tourney, Littlefinger has opened up the possibility of Sansa having a key tactical advantage over him; especially when he later leaves it up to her to decide which knight will receive her favour. However, we cannot disregard LF’s own plans for this event, which are certain to be more complex and far-reaching than finding eight winged knights to act as Robert Arryn’s protectors.

Vile princes and kings

In The Hedge Knight, Ser Duncan the Tall attends the tourney in honour of Lord Ashford’s daughter who is celebrating her 13th birthday. This is the same age Joffrey turns when his own name day tourney is held in A Clash of Kings, and whose increasingly cruel behaviour calls to mind the disturbed nature of the Targaryen prince, Aerion Brightflame, who will maim Humfrey Hardyng at Ashford and later fight Dunk in a trial by seven after the hedge knight comes to the rescue of Tanselle Too Tall. Compare Aerion’s cruel treatment of Tanselle with Joff’s violence against Sansa and the disturbing parallel is all too clear:

The dragon puppet was scattered all about them, a broken wing here, its head there, its tail in three pieces. And in the midst of it all stood Prince Aerion, resplendent in red velvet doublet,

with long, dagged sleeves, twisting Tanselle’s arm in both hands. She was on her knees, pleading

with him. Aerion ignored her. He forced open her hand and seized one of her fingers. Dunk stood

there stupidly, not quite believing what he saw. Then he heard a crack, and Tanselle screamed.

(The Hedge Knight)

Knowing that Joffrey would require her to attend the tourney in his honor, Sansa had taken special care with her face and clothes. She wore a gown of pale purple silk and a moonstone hair net that had been a gift from Joffrey. The gown had long sleeves to hide the bruises on her arms. Those were Joffrey’s gifts as well. When they told him that Robb had been proclaimed King in the North, his rage had been a fearsome thing, and he had sent Ser Boros to beat her.

(Sansa I, ACOK)

It’s noteworthy that Sansa, like Dunk, performed her own brand of heroics at Joffrey’s tourney, when she convinced him not to kill the drunken knight Ser Dontos. Whilst the Vale tourney is mercifully free from the spectre of princely ire and madness, there are some characters that display the same kind of arrogance and hot-headed nature which could prove troublesome on the day. Sansa notes in particular the simmering rage of Ser Lyn Corbray. Couple this with the fact that Martin seems to be fond of having knights from the Vale meet their deaths at tournaments – in addition to Ser Humfrey at Ashford is the killing of Ser Hugh by Gregor Clegane at the Hand’s tourney – and we could be in for a similarly violent spectacle at the Gates. Relevant to this discussion is the theory that Littlefinger may have also played a role in the killing of Ser Hugh in order to thwart Ned Stark’s investigation into Jon Arryn’s death. This speculation is not unfounded given the other heartless tactics we have seen LF employ throughout the series.

Sansa’s position in the Vale is not like the one she occupied in KL – vulnerable and at the mercy of Joffrey’s cruel whims — yet she is not completely out of the woods as it relates to those who might try to do her harm. Martin has set up the likes of Corbray and Ser Shadrich as unpredictable characters, and there’s no telling how much Sansa’s true identity remains more of an open secret at this point.

The Ashford tourney ends in a trial of seven with Dunk and Aerion Brightflame fighting against each other alongside their respective champions. Notably, Catelyn witnessed a trial by combat at the Eyrie, and Sansa’s experiences there have tracked closely to her mother’s. During that trial between Tyrion’s champion Bronn and Ser Vardis Egen, Sweetrobin’s behaviour recalls the kind of infantile bloodlust exhibited by Joffrey, who also loved to suggest making men fight to the death:

“Make them fight!” Lord Robert called out.

Ser Vardis faced the Lord of the Eyrie and lifted his sword in salute. “For the Eyrie and Vale!”

Tyrion Lannister had been seated on a balcony across the garden, flanked by his guards. It was to him that Bronn turned with a cursory salute.

“They await your command,” Lady Lysa said to her lord son.

“Fight!” The boy screamed, his arms trembling as they clutched at his chair.

As the fighting ensues, Cat remembers the duel fought between LF and Brandon Stark, her betrothed, who agreed to spare the young Petyr on her behalf. Since then, LF claims to have learnt his lesson about his lack of martial prowess, but it’s worth considering if he could face a similar trial by combat in the Vale (or Winterfell) if his crimes are made known to the Lords there, and Sansa certainly has no similar incentive to spare him as her mother did. Perhaps SR will eventually get his wish to see the “bad little man” fly.

Sansa’s tourney and Littlefinger’s Plans

We learn in the sample chapter that the Vale tournament is being staged for the honour of serving as a member of Lord Robert’s Winged Knights:

Lord Robert’s mother had filled him full of fears, but he always took courage from the tales she read him of Ser Artys Arryn, the Winged Knight of legend, founder of his line. Why not surround him with Winged Knights? She had thought one night, after Sweetrobin had finally drifted off to sleep. His own Kingsguard, to keep him safe and make him brave.

It is a novel idea for a tourney up to this point in the series and one that aims to placate the irritable and insecure young Lord of the Eyrie. However, as the chapter develops, the curious fact emerges that this is an event seeming designed more to honour Sansa Stark than her cousin. I say Sansa Stark and not Alayne Stone deliberately, because the evidence suggests that Littlefinger has plans to declare her true identity. It is here that the past tourneys prove quite useful to study for elucidating the hidden workings at play in Sansa’s chapter, with precedent already set in Martin’s universe for a tourney that conceals its true purpose: the attempted Second Blackfyre rebellion in The Mystery Knight, which masqueraded as a mere wedding celebration for Lord Butterwell and his Frey bride.

The first hint that we have concerns Sansa’s thoughts about the tourney itself, which repeatedly highlight her role in its conception and organisation. It is a point of considerable pride for her:

The competitors came from all over the Vale, from the mountain valleys and the coast, from Gulltown and the Bloody Gate, even the Three Sisters. Though a few were promised, only three were wed; the eight victors would be expected to spend the next three years at Lord Robert’s side, as his own personal guard (Alayne had suggested seven, like the Kingsguard, but Sweetrobin had insisted that he must have more knights than King Tommen), so older men with wives and children had not been invited.

And they came, Alayne thought proudly. They all came.

It had fallen out just as Petyr said it would, the day the ravens flew. “They’re young, eager, hungry for adventure and renown. Lysa would not let them go to war. This is the next best thing. A chance to serve their lord and prove their prowess. They will come. Even Harry the Heir.” He had smoothed her hair and kissed her forehead. “What a clever daughter you are.”

It was clever. The tourney, the prizes, the winged knights, it had all been her own notion.

Is LF complimenting Sansa for her own sake here, or is his pride in her cleverness because it serves to further his own ends? That he has repeatedly misled her and exploited her ignorance of his true intentions makes a strong argument for the latter interpretation. Regardless, Sansa has taken personal responsibility for this tourney, and it is closely linked with her particular desires and personal history – not Alayne’s. Sourcing knights to serve SR looks to only be a thin cover for a tourney that will have much bigger implications for its hostess.

The conversation Sansa has with Littlefinger when she journeys below to the vaults provides additional evidence that something is afoot regarding her true identity and the real purpose for staging this event. As LF attempts to calm her anxiety regarding Harry, we read:

“…Bringing Harry here was the first step in our plan, but now we need to keep him, and only you can do that. He has a weakness for a pretty face, and whose face is prettier than yours? Charm him. Entrance him. Bewitch him.”

“I don’t know how,” she said miserably.

“Oh, I think you do,” said Littlefinger, with one of those smiles that did not reach his eyes. “You will be the most beautiful woman in the hall tonight, as lovely as your lady mother at your age. I cannot seat you on the dais, but you’ll have a place of honor above the salt and underneath a wall sconce. The fire will be shining in your hair, so everyone will see how fair of face you are. Keep a good long spoon on hand to beat the squires off, sweetling. You will not want green boys underfoot when the knights come round to beg you for your favor.”

There are two important points relating to Sansa’s identity in this exchange with LF. Firstly, he mentions her resemblance to Catelyn, a direct association between Sansa and her mother that highlights her real parentage. Secondly, and more subtly, he notes that the “fire will be shining in your hair” – a very suggestive description that alludes to Sansa’s natural auburn colour showing once again. It all results in the impression that Sansa is looking very much like Sansa again and, more importantly, that LF doesn’t seem all that concerned about hiding this from the gathered guests. Another intriguing possibility raised by readers is that LF is slipping, that his obsession with his Catelyn proxy is quite literally blinding him to her identity as Sansa Stark which will come back to bite him/could have profound consequences at the tourney. To extend this latter reading, let’s look at the parallel to their first meeting at the Hand’s tourney in King’s Landing:

When Sansa finally looked up, a man was standing over her, staring. He was short, with a pointed beard and a silver streak in his hair, almost as old as her father. “You must be one of her daughters,” he said to her. He had grey-green eyes that did not smile when his mouth did. “You have the Tully look.”

“I’m Sansa Stark,” she said, ill at ease…

“Your mother was my queen of beauty once,” the man said quietly. His breath smelled of mint. “You have her hair.” His fingers brushed against her cheek as he stroked one auburn lock. Quite abruptly he turned and walked away.

The pertinent details relate to LF’s complete association of Sansa to her mother, whom he states was once his “queen of beauty.” Stroking a lock of Sansa’s auburn hair reinforces how much she looks like Catelyn and the attraction it sparks in him as a result. However, notice Sansa’s interjection that LF seemingly does not even hear or chooses to ignore. She asserts that “I’m Sansa Stark” after he tells her she has the Tully look and feels “ill at ease.” I want to stress that the two theories explaining Sansa’s conversation with LF in the vaults — he is aware of her auburn hair showing and wants to highlight it vs. he continues to over-identify Sansa with her mother and what this reveals about his ultimate plans (and their likely success or failure) — are not mutually exclusive. Indeed, it could be argued that it is LF’s obsessive compulsion to regain what he believes should have been his in the first place, along with all the power and privilege he can accrue, that is the governing principle behind all the chaos he has unleashed.

The feast in the night where Sansa holds court as LF promises also has parallels to other major feasts we have seen in the series. The similarity to the Purple Wedding with the extravagant number of dishes has been noted by other commenters, with the inherent symbolism of wastefulness and contempt for the starving populations across Westeros. To begin with the Hand’s tourney, however, we see some telling similarities – right down to the type of dessert served:

Six monstrous huge aurochs had been roasting for hours, turning slowly on wooden spits while kitchen boys basted them with butter and herbs until the meat crackled and spit. Tables and benches had been raised outside the pavilions, piled high with sweetgrass and strawberries and fresh-baked bread…

All the while the courses came and went. A thick soup of barley and venison. Salads of sweetgrass and spinach and plums, sprinkled with crushed nuts. Snails in honey and garlic. Sansa had never eaten snails before; Joffrey showed her how to get the snail out of the shell and fed her the first sweet morsel himself. Then came trout fresh from the river, baked in clay; her prince helped her crack open the hard casing to expose the flaky white flesh within. And when the meat course was brought out he served her himself, slicing a queen’s portion from the joint, smiling as he laid it on her plate…

Later came sweetbreads and pigeon pie and baked apples fragrant with cinnamon and lemon cakes frosted in sugar, but by then Sansa was so stuffed that she could not manage more than two little lemon cakes, as much as she loved them. She was wondering whether she might attempt a third when the king began to shout. (Sansa II, AGOT)

———-

Sixty-four dishes were served, in honor of the sixty-four competitors who had come so far to

contest or the silver wings before their lord. From the rivers and the lakes came pike and trout and salmon, from the seas crab and cod and herring. Ducks there were, and capons, peacocks in their plumage and swans in almond milk. Suckling pigs were served up crackling with apples in their mouths, and three huge aurochs were roasted whole above the firepits in the castle yard, since they were too big to get through the kitchen doors. Loaves of hot bread filled the trestle tables in Lord Nestor’s hall and massive wheels of cheese were brought up from the vaults. The butter was fresh-churned, and there were leeks and carrots, roasted onions, beets, turnips, parsnips. And best of all, Lord Nestor’s cooks prepared a splendid subtlety, a lemon cake in the shape of the Giant’s Lance, twelve feet tall and adorned with an Eyrie made of sugar.

For me, Alayne thought, as they wheeled it out. Sweetrobin loved lemon cakes too, but only after she told him that they were her favorites. The cake had required every lemon in the Vale, but Petyr had promised that he would send to Dorne for more. (Alayne sample, TWOW)

So at both feasts we see Sansa being served with lemoncakes frosted in sugar, the first time when she still expects to eventually become Joffrey’s queen. Lemons in the series have been associated with innocence, childhood, and longing for a return to happier times. Daenerys thinks fondly, for example, of the house with the lemon tree in Braavos. For Sansa’s characterisation, however, whilst lemons do undoubtedly hold a similar kind of symbolism due to her childlike devotion to them, whenever she is served them by others there is always some deception and manipulation involved. In studying the references to lemoncakes in her arc, the pattern is revealing:

- At the Hand’s tourney, Joffrey begins to treat Sansa more kindly again and she is unaware of his true nature. Readers know that Joffrey isn’t at all what he seems, and his indulgent attention to Sansa is only a momentary guise of gallantry. Sansa is already “stuffed” by the time the lemoncakes arrive, but her love of them leads her to at least attempt eating a few. We will see Sansa make a similarly concentrated attempt to believe in Joffrey’s goodness until his base cruelty is revealed when he kills her father.

- In the chapter where Sansa remembers the next encounter she has with Littlefinger at court, she and Jeyne go looking for lemon cakes but have to settle for strawberry pie. Here we see the lack of lemon cakes symbolising the absence of any retreat into familiar reassurances/safety where LF is concerned. When she tells him of her belief in “monsters and heroes” for the reason why Ned should have sent Loras Tyrell to kill Gregor Clegane, his reply leaves her deeply unsettled: “Life is not a song, sweetling. You may learn that one day to your sorrow.”

- In A Storm of Swords, Sansa meets with the Tyrell family and is given the hope of marriage to Willas Tyrell and freedom from the Lannisters. During her initial meeting with them and after, we read of the frequent consumption of lemon cakes, as she comes to think of the Tyrell women as true friends and allies:

“Sansa,” Lady Alerie broke in, “you must be very hungry. Shall we have a bit of boar together, and some lemon cakes?”

“Lemon cakes are my favourite,” Sansa admitted.

“So we have been told,” declared Lady Olenna, who obviously had no intention of being hushed. “That Varys creature seemed to think we should be grateful for the information…” (Sansa I, ASOS)

———-

The cousins took Sansa into their company as if they had known her all their lives. They spent long afternoons doing needlework and talking over lemon cakes and honeyed wine, playing at tiles of an evening, sang together in the castle sept… and after one or two of them would be chosen to share Margaery’s bed, where they would whisper half the night away.

(Sansa II, ASOS)

Alerie’s suggestion of boar and lemon cakes highlights the dual symbolism of regime change by ultimately plotting Joffrey’s murder and their plans to take advantage of Sansa’s status and claim for their own ends. As Sansa will learn when she is forcefully wed to Tyrion Lannister, the Tyrells were never genuinely her friends, and once she is no longer available to be married into their family, they cease their association with her.

- The next time lemon cakes are mentioned in Sansa’s chapters occurs in A Feast for Crows, when she promises them to Sweetrobin as an inducement to get him out of bed to depart the Eyrie before winter closes in. Once they arrive at the Gates of the Moon and she is ushered in to Littlefinger’s solar, Sansa mentions lemons as one of her guesses on LF’s prompting:

“I have brought my sweet girl back a gift.”

Alayne was as pleased as she was surprised. “Is it a gown?” She had heard they were fine seamstresses in Gulltown, and she was so tired of dressing drably.

“Something better. Guess again.”

“Jewels?”

“No jewels could hope to match my daughter’s eyes.”

“Lemons? Did you find some lemons?” She had promised Sweetrobin lemon cake, and for lemon cake you needed lemons.

Petyr Baelish took her by the hand and drew her down onto his lap. “I have made a marriage contract for you.”

“A marriage…” Her throat tightened. She did not want to be wed again, not now, perhaps not ever.

Once again, we see Sansa’s attempt to normalise the circumstances of her relationship with LF fail. This is highlighted by the symbolic lack of lemon cakes, which she had hoped to secure for Sweetrobin, but is instead met with the news of another marriage pact that understandably reawakens her fears of exploitation and loss of agency.

Taken all together, the lemon cake references provide us with the symbolic clues through which to view the appearance of the giant lemon cake lance at the feast in TWOW. LF is attempting to manipulate Sansa, but this time it is no ordinary machination. After all, the cake has taken every single lemon in the Vale to bake it, suggesting that whatever LF has in mind it is going to considerably momentous. As noted, lemon cakes in Sansa’s arc strongly correspond to the theme of appearance vs. reality as it relates to people hiding their true intentions or character. It raises the question of just what LF is planning; why has he used every lemon in the Vale to bake a cake for Alayne at a public event, when it is widely known as Sansa Stark’s favourite dessert? Why did he readily agree to organise this elaborate event at the Gates of the Moon, inviting young knights sworn to the Vale and hosting them with no expense spared?

An answer to these questions might be found in that last AFFC chapter when LF tells Sansa about the marriage pact. Right before this, he makes a very cryptic remark that has been the subject of much speculation:

“You would not believe half of what is happening in King’s Landing, sweetling. Cersei stumbles from one idiocy to the next, helped along by her council of the deaf, the dim, and the blind. I always anticipated that she would beggar the realm and destroy herself, but I never expected she would do it quite so fast. It is quite vexing. I had hoped to have four or five quiet years to plant some seeds and allow some fruits to ripen, but now…it is a good thing I thrive on chaos. What little peace and order the five kings left us will not long survive the three queens, I fear.”

“Three queens?” She did not understand.

Nor did Petyr choose to explain.

There are a couple reasons to speculate that LF has included Sansa as one of these three warring queens he mentions. In examining his statement closely, we glean that LF is not merely speaking abstractly about coming events that have nothing to do with him. Instead, he implicates himself directly by stating that he had hoped for more time to allow “some fruits to ripen” but that he thrives on chaos. I’d argue that the fruit he was most interested in ripening was Sansa Stark herself, allowing her to further mature, and giving himself time to have her completely under his thumb. The next reason is that he very deliberately chooses not to inform Sansa of the identities of these three queens. Instead, he goes on to tell her of the marriage pact which ends with the promise of retaking Winterfell once she marries Harry the Heir and Sweetrobin dies. Refusing to answer Sansa’s query suggests that Littlefinger has something to hide, and the most plausible answer to why he has something to hide is because it involves Sansa – in a much more prominent role than she could ever imagine.

If LF is planning to declare Sansa as Queen of the North, he could hardly have chosen a more auspicious place to do so. The tourney, with its knights hungry for service and eager for honour, seems tailor-made for making a declaration of a new queen — the last known remaining Stark and rightful ruler of the North — especially when the houses of the Vale had been eager to fight for Robb but denied by Lysa Arryn. Sansa becoming a queen also ties together the foreshadowing of her thoughts when she is with Cersei in the Red Keep – “If I am ever a queen, I’ll make them love me” – and when she meets Bronze Yohn Royce at the Eyrie and thinks that he never fought for Robb, so why would he fight for her.

Before we move onto looking at more food symbolism at the other feasts, there’s another aspect to the lemon cakes that bears brief exploration as I think it presents us with foreshadowing of Littlefinger attempting to make a marriage alliance with the newly landed Aegon, who alleges to be Rhaegar Targaryen’s son:

The cake had required every lemon in the Vale, but Petyr had promised that he would send to Dorne for more.

In Arianne’s two chapters from TWOW, we learn that she is on her way to meet with Aegon on behalf of Dorne, in order to ascertain whether he is truly Rhaegar’s heir. The letter that Connington sends to Doran reads as follows:

To Prince Doran of House Martell,

You will remember me, I pray. I knew your sister well,

and was a leal servant of your good-brother. I grieve

for them as you do. I did not die, no more than did

your sister’s son. To save his life we kept him hidden,

but the time for hiding is done. A dragon has returned

to Westeros to claim his birthright and seek vengeance

for his father, and for the princess Elia, his mother.

In her name I turn to Dorne. Do not forsake us.

Jon Connington

Lord of Griffin’s Roost

Hand of the True King

With the evidence pointing to lemon cakes being tied to underhanded/manipulative situations in Sansa’s story, Petyr’s sending to Dorne for more lemons suggests him attempting to make an alliance with the one other region outside of the Vale that has not yet entered the war. Right now, Dorne’s decision hinges on what Arianne reports back to her father about Aegon’s identity and chances of success in claiming the Iron Throne. With Dany out of the picture for the time being, a marriage alliance to Sansa Stark of the North, who can deliver the Vale swords would be quite an advantageous match for the young prince.

Sansa’s TWOW chapter hints at important news having reached Littlefinger via Oswell, who arrives from Gulltown on a “lathered horse.” In looking at the ASOIAF timeline, Sansa’s descent from the Eyrie happened in the middle of May, and we know her chapter in TWOW picks up several months later, as she observes that “though snow had blanketed the heights of the Giant’s Lance above, below the mountain the autumn lingered and winter wheat was ripening in the fields.” If we assume an approximate date of late summer/early fall, Sansa’s TWOW chapter puts us somewhere near the middle to late August, and according to the timeline, Arianne learns of Aegon having taken Storm’s End around July 17th. All this means that it is possible for LF to know of Aegon and his success so far with the Golden Company.

Having considered this, it’s important to point out that the lemon cake associated betrothals for Sansa have all failed. She doesn’t end up having to marry Joffrey, and the Willas match is discovered by the Lannisters, leading to forced union with Tyrion Lannister, which as yet still protects her from any other marriages taking place. Martin also seems to be playing with the tourney imagery in having Aegon meet with yet another “Elia” in Oberyn Martell’s bastard daughter Elia Sand, who is nicknamed “Lady Lance” and is skilled at riding and jousting. Of course, it is the wolf-maid Sansa who is organising an actual tourney that could result in her being crowned as queen, following in the tradition of her aunt Lyanna Stark, whom Rhaegar chose over Elia as his queen of love and beauty. This reversal could see Elia being the one to secure Aegon’s affection and Sansa ultimately avoiding a return to Southron politics and game-playing as Aegon’s sure to be ill-fated wife.

Roasted peacocks and boar

The Mystery Knight details the attempted Second Blackfyre Rebellion, where lords still loyal to Black dragons gathered at Whitehalls in order to plot to overthrow the Targaryen king and seat Daemon II Blackfyre on the throne. On the basis of the “secret heir in disguise with sympathetic lords all around” alone, we can see a direct link to Sansa’s situation at the Gates.

One of the early hints we have of the planned regime change in the novella is when boar is served at the inn where Dunk and Egg hope to eat and rest, but are instead turned away and have to seek shelter with three hedge knights nearby:

A good smell was drifting out the windows of the inn, one that made Dunk’s mouth water. “We might like some of what you’re roasting, if it’s not too costly.”

“It’s wild boar,” the woman said, “well-peppered, and served with onions, mushrooms, and mashed neeps.”

Once at the castle, Dunk attends the wedding feast and the similarities between the dishes there and at Sansa’s pre-tourney feast are striking:

Suckling pig was served at the high table; a peacock roasted in its plumage; a great pike crusted with crushed almonds. Not a bite of that made it down below the salt. Instead of suckling pig they got salt pork, soaked in almond milk and peppered pleasantly. In place of peacock they had capons, crisped up nice and brown and stuffed with onions, herbs, mushrooms and roasted chestnuts. In place of pike they ate chunks of flaky white cod in a pastry coffyn, with some sort of tasty brown sauce that Dunk could not quite place. There was pease porridge besides; buttered turnips; carrots drizzled with honey; and a ripe white cheese that smelled as strong as Bennis of the Brown Shield. (The Mystery Knight)

———-

Sixty-four dishes were served, in honor of the sixty-four competitors who had come so far to contest for silver wings before their lord. From the rivers and the lakes came pike and trout and salmon, from the seas crabs and cod and herring. Ducks there were, and capons, peacocks in their plumage and swans in almond milk. Suckling pigs were served up crackling with apples in their mouths, and three huge aurochs were roasted whole above firepits in the castle yard, since they were too big to get through the kitchen doors. Loaves of hot bread filled the trestle tables in Lord Nestor’s hall, and massive wheels of cheese were brought up from the vaults. The butter was fresh-churned, and there were leeks and carrots, roasted onions, beets, turnips, parsnips. (Alayne sample, TWOW)

Out of this bounty of food porn, a few dishes standout: the “peacocks in their plumage,” “suckling pigs,” and the “great pike crusted with crushed almonds.” These are all the dishes that are served for the nobles at Whitehalls, or above the salt as Dunk observes, and we see them again featured at the pre-tourney feast in the Vale. Leaving aside the latter two for now, I want to focus on the peacock entrée, because in addition to these examples, it is mentioned only one other time in the series – at the Purple Wedding.

Then the heralds summoned another singer; Collio Quaynis of Tyrosh, who had a vermillion beard and an accent as ludicrous as Symon had promised. Collio began his version of “The Dance of Dragons” which was more properly a song for two singers, male and female. Tyrion suffered through it with a double helping of honey-ginger partridge and several cups of wine. A haunting ballad of two dying lovers amidst the Doom of Valyria might have pleased the hall more if Collio had not sung it in High Valyrian, which most of the guests could not speak. But “Bessa the Barmaid” won them back with ribald lyrics. Peacocks were served in their plumage, roasted whole and stuffed with dates, while Collio summoned a drummer, bowed low before Lord Tywin, and launched into the “The Rains of Castamere.”

Given how the Purple Wedding ends – Joffrey’s death, Tyrion framed for the murder – “peacocks roasted in the plumage” appears to be symbolic of those who are killed or undermined at a moment of celebration or impending victory. The same is evident for the conspirators at the Whitehalls tourney, who are discovered before their rebellion can gain any traction. The saying “to strut around like a peacock” is to display an attitude of overt pride and confidence that borders on arrogance. The plumage of the peacock — its impressive display of brightly coloured feathers – is the symbol of that pride, and as it so happens, there is one character in Sansa’s arc who has a noted preference for brightly coloured, almost gaudy clothing throughout the series. Is LF the only peacock at the Vale whose plans might be upset? He’s certainly the most major one, yet there are other potential candidates like Ser Lyn Corbray, last seen bashing in the head of a hapless knight, or someone like Harry the Heir, whose initial sneering at Sansa and poor jousting skills don’t bode well for his prospects as either a suitor or champion. We also cannot discount the appearance of an outside force, such as the Mountain clans – newly armed with steel weaponry – who could find a way to infiltrate the Gates and cause widespread destruction, thereby “roasting” the many peacocks represented by the knightly gathering.

If our food symbolism is to bear out, it stands to reason that as we see boar being roasted in The Mystery Knight, it should also be present at the Purple Wedding and in Sansa’s pre-tourney chapter. Tyrion is our gastronomical guide during the excesses of Joffrey’s wedding feast, and sure enough we find this line as he indulges his appetite:

Tyrion listened with half an ear, as he sampled sweetcorn fritters and hot oatbread backed with bits of date, apple, and orange, and gnawed on the rib of a wild boar.

Yet we have no mention of boar being eaten at the pre-tourney feast in TWOW or anywhere else in the chapter. My theory is that instead of highlighting boars at the feast, Martin has cleverly depicted these wild animals in another location, which Alayne casually calls to our attention by way of walking through the castle on her way to locating Littlefinger:

Alayne swept down the tower stairs to enter the pillared gallery at the back of the Great Hall. Below her, serving men were setting up trestle tables for the evening feast, while their wives and daughters swept up the old rushes and scattered fresh ones. Lord Nestor was showing Lady Waxley his prize tapestries, with their scenes of hunt and chase. The same panels had once hung in the Red Keep of King’s Landing, when Robert sat the Iron Throne. Joffrey had them taken down and they had languished in some cellar until Petyr Baelish arranged for them to be brought to the Vale as a gift for Nestor Royce. Not only were the hangings beautiful, but the High Steward delighted in telling anyone who’d listen that they had once belonged to a king.

Hunt and chase — the very activity that leads to Robert’s death, and a favourite pastime of the King’s that Ned recalls in AGOT as he tries to comfort the despondent Barristan Selmy:

“Even the truest knight cannot protect a king against himself,” Ned said. “Robert loved to hunt boar. I have seen take him a thousand of them.” He would stand his ground without flinching, his legs braced, the great spear in his hands, and as often as not he would curse the boar as it charged, and wait until the last possible second, until it was almost on him, before he killed it with a single sure and savage thrust.

Other mentions of the tapestries all reinforce the hunting imagery. In the throne room right before Ned’s arrest, he observes the gold cloaks, standing by the walls “in front of Robert’s tapestries with their scenes of hunt and battle”. Later on, Sansa will observe the throne room “stripped bare, the hunting tapestries that King Robert loved taken down and stacked in the corner in an untidy heap.” The Vale declaring for Sansa as Queen of the North would represent a significant regime change that threatens the Lannister/Tyrell power in the South; even more so if the Vale decides to enter the war and fight on Aegon’s behalf. Yet, it’s worth noting that the mere nature of “hunt and chase” for the boar symbolism could indicate that LF loses control of the regime change he has put into motion. Unlike at his wedding to Lysa Arryn, where roast boar is served and she later meets a tragic end through the moon door, this one might not turn out to be so straightforward to engineer and direct.

The Mystery Knights of the Vale

“Every wedding needs a singer, and every tourney needs a mystery knight.”

Ser John the Fiddler

If we are to adhere to the Fiddler’s declaration in the above statement, Martin is overdue in writing of a mystery knight making an appearance at a tournament. The only ones we are privy to in some detail are the Knight of the Laughing Tree – widely considered in the fandom to be Lyanna Stark – and Dunk as the Gallows Knight. The appearance of a mystery knight in the lists at the Vale tourney would seem to be unlikely given that all the competitors have been specially invited and all appear to be accounted for at this point in time. Yet, the parallels between Sansa’s TWOW chapter and The Mystery Knight, coupled with her familial connection to Lyanna and what we learn of how the Harrenhal tourney plays out, make for a convincing case that Martin will feature a mystery knight in the Vale in some form or fashion.

In A Storm of Swords, Meera tells Bran about the story of the Knight of the Laughing Tree, who appears as a mystery knight at the Harrenhal tourney and challenges the knights whose squires were responsible for hurting a crannogman from the Neck. Bran listens to the story and thinks:

Mystery knights would oft appear at tourneys, with helms concealing their faces, and shields that were either blank or bore some strange device. Sometimes they were famous champions in disguise. The Dragonknight once won a tourney as the Knight of Tears, so he could name his sister the queen of love and beauty in place of the king’s mistress. And Barristan the Bold twice donned a mystery knight’s armor, the first time when he was only ten.

The Mystery Knight novella features Dunk appearing as the Gallows Knight, and other characters that are also concealing their true identities and motives. There is Ser John the Fiddler, who is really Daemon II Blackfyre; Ser Glendon Flowers, who reveals that he is the illegitimate son of Ser Quentyn Ball; and Ser Maynard Plumm, who is most likely Bloodraven under the disguise of a glamor. Dunk eventually discovers and helps to scuttle the plans of the conspirators at the tourney, who are using the wedding to secretly plot a rebellion against Aerys I.

This is likely Martin’s last chance to introduce a mystery knight at a tourney in the series, and he has already established a suspicious cast of characters around Sansa in the Vale who could play important roles in how the plot unfolds there. We may not get to see the classic mystery knight figure that Bran recalls, but there are a few candidates who are worthy of consideration, both for their current proximity to Sansa, and others who are relevant because of their shared personal history and connection to the relevant themes in her development.

Contenders inside the Vale:

Ser Shadrich, Ser Morgarth, Ser Byron: It’s safe bet that the three hedge knights Alayne meets when she descends the Eyrie are not telling the truth about their real identities/motives. We already know that Shadrich is a bounty hunter on the lookout for Sansa Stark, and appears to know he has found her by his comments in TWOW:

“A good melee is all a hedge knight can hope for, unless he stumbles on a bag of dragons. And that’s not likely, is it?”

Regular followers of Pawn to Player would be familiar with our theory that Ser Morgarth is really the Elder Brother from the QI. Sansa also dances with all three of the hedge knights at the feast, so Martin does appear to be keeping them at the forefront of our thoughts for a reason.

Ser Lyn Corbray

The wielder of Lady Forlorn has to be considered as another contender based on Sansa’s observations that he appears to hold a significant amount of genuine dislike against LF for arranging his brother’s marriage, even though he is supposedly working for LF’s interests in secret. Lyn is a highly ambitious man and is obviously not content with gold and boys. If he acts to undermine LF at the tourney, it could prove disastrous for the mockingbird.

Sansa’s champion

Who is the knight that Sansa will select to wear her favour? It’s a seemingly inconsequential choice as suggested by LF, who merely tells her to choose another so not as to overly flatter Harry. But is it merely a trivial detail for Sansa? Throughout the series, Sansa has prayed for a true knight or champion at different moments of crisis, and has been uniformly disappointed by the ones that appeared to care for her or genuinely want to help her. There is no better example of the ruined institution of knighthood than the Kingsguard, who were routinely employed by Joffrey to abuse Sansa in King’s Landing. Although she no longer holds the naïve view of knights being essentially good and honourable, it does not mean that the knight Sansa chooses to wear her favour may not still represent the greater potential of that ideal. Regardless of the basis upon which she makes her decision, Sansa has the chance to make an autonomous choice that could have significant consequences. (Incidentally, LF does not have good luck when it comes to favours; Cat gave her handscarf to Brandon in the fight against him at Riverrun, after Petyr pleaded with her to give him her favour instead.)

Contenders outside the Vale:

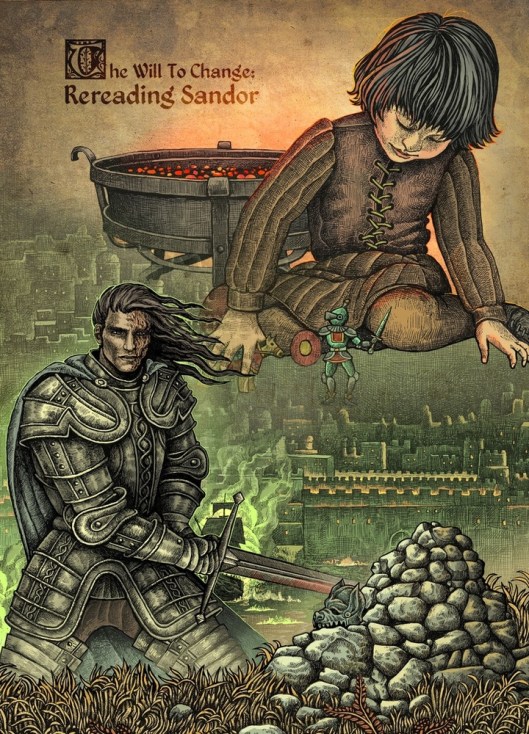

Sandor Clegane

Any speculation of mystery knights in Sansa’s arc would be remiss not to include Sandor Clegane. Last seen performing gravedigging duties at the Quiet Isle, Sandor is not believed to be in the Vale; however, present or not at this tourney, Sandor is the one who has consistently acted as Sansa’s champion during their time together. The Hound is famous for his opinions on the hypocrisy and falsity of knighthood, and undoubtedly is responsible for much of the enlightenment and maturity Sansa achieves over time. But their relationship is a two-way street, with Sansa having just as much, if not more, of an impact on his character development; arguably being a major deciding factor in his break from the Lannisters, and inspiring the desire to be his “own dog now.” The Elder Brother tells us that the Hound is dead, while Sandor Clegane is “at rest.” This distinction sets up an interesting identity angle for Martin to explore, in addition to the false rumours of the Hound being responsible for the atrocities at Saltpans necessitating a need for continued concealment on Sandor’s part.

Having played notable roles at the two previous tourneys in the series, both of them involving close contact with Sansa and providing crucial assistance to her, it begs the question if an appearance by Sandor at the third such event isn’t of vital importance to the narrative structure and thematic continuity of their relationship. I would argue that this is why he is conspicuously absent from the pre-tourney chapter in Sansa’s thoughts. Whether he makes a physical return or Sansa recalls a memory about him, Martin intends for it to be of some import.

Sandor’s significance as a mystery non-knight for Sansa is perhaps most invaluable because Littlefinger does not know about it. Not only does she venerate Sandor in terms of truth-telling, but Martin has established a romantic connection between the two that has managed to persist despite a long separation. One of LF’s primary means of control over Sansa is to constantly set up but ultimately undermine any potential suitor or love interest. It’s one of the reasons why I expect the Harry the Heir betrothal to come to naught. LF’s obsession with Sansa, arising from the denial of Catelyn who was his primary love object, causes him to compulsively repeat the act of vanquishing a rival. As the tourney is arranged, LF plainly does not expect any surprises regarding Sansa’s affections, believing that he has successfully manipulated and monopolized her attention with Harry the Heir.

Where matters of the heart are concerned, tourneys can be game changers, and this is why his gamble with Sansa’s favour could backfire. Recall the Hand’s tourney when LF is so certain that the Hound will lose to Jaime Lannister because “hungry dogs know better than to bite the hand that feeds them.” It turned out that Sandor Clegane didn’t know any better, and LF loses his bet to Renly Baratheon. Since then, we have to ask ourselves if LF has gotten any wiser regarding what truly motivates and inspires others. Taking Lyn Corbray as a case study, the answer appears to be no. When at the Fingers, LF poses a question to Sansa, asking: “which is more dangerous, the knife brandished by an enemy or the hidden dagger pressed to your back that you never even see?” What would he have to say about the hidden rival?

Bran Stark

The idea of Bran Stark influencing events in Sansa’s storyline is a compelling one for many reasons. As things stand in the present, Bran is the one Stark with the growing powers to reach out to his siblings and gain insight into their respective circumstances, opening up the possibility that he could be a source of assistance in the future. As Bloodraven promises him in the cave:

Once you have mastered your gifts, you may look where you will and see what the trees have seen, be it yesterday or last year or a thousand years past… Nor will your sight be limited to your godswood. The singers carved eyes into their heart trees to awaken them, and those are the first eyes a new greenseer learns to use… but in time you will see well beyond the trees themselves.

It’s been noted that the “winged knight” tourney could be thought of as an allusion to Bran, and readers are privy to his continued longing for the dreams of knighthood he held as a young boy. Even as late as ADWD, we see him expressing the sorrow of ultimately becoming like his mentor:

One day I will be like him. The thought filled Bran with dread. Bad enough that he was broken, with his useless legs. Was he doomed to lose the rest too, to spend all of his years with a weirwood growing in him and through him? … I was going to be a knight, Bran remembered. I used to run and climb and fight. It seemed a thousand years ago.

What was he now? Only Bran the broken boy, Brandon of House Stark, prince of a lost kingdom, lord of a burned castle, heir to ruins… A thousand eyes, a hundred skins, wisdom as deep as the roots of ancient trees. That was as good as being a knight. Almost as good, anyway.

None of this offers conclusive evidence of a Bran intervention, but it does align him thematically with what is happening currently in the Vale, especially when we factor in the story of the Knight of the Laughing Tree. Bran likes the tale, but has ideas for how it could be even better:

“That was a good story. But is should have been the three bad knights who hurt him, not their squires. Then the little crannogman could have killed them all. The part about the ransoms was stupid. And the mystery knight should win the tourney, defeating every challenger, and name the wolf-maid the queen of love and beauty.”

The wolf-maid becoming queen of love and beauty is what happened to Lyanna Stark, whereas there’s the possibility of Sansa becoming an actual queen by the end of her tourney. Could a mystery knight be the one to undermine LF’s plans and steal the wolf-maid away as Rhaegar Targaryen is alleged to have done with Sansa’s aunt?

Final observations:

Pawn to Player has never been in the business of the making predictions, so I will refrain from making any explicit ones and stick to what this all means for Sansa’s character development. Like all the Stark children, Sansa is under the guidance of a dubious and duplicitous mentor, but the Vale is where we see her maturing and honing the skills that should allow her to break free of LF’s influence. Becoming a queen is not Sansa’s endgame in the sense of her ruling the North in her own right or acting as a queen consort to a King. Sansa’s arc has tracked towards self-empowerment not traditional institutional power. It is about her ultimately possessing the agency and authority to decide what it is she wants and how she can effectively help others. It is about her no longer being manipulated and exploited by those around her. If there’s one thing we know about wearing crowns in ASOIAF is that the likelihood of that manipulation only increases. Sansa’s brothers are still alive and there is Robb’s will that has not yet surfaced naming Jon as his successor. If Sansa is to become queen in this interim period, then her control of the Vale army will have important ramifications for how the remainder of the unrest in Westeros plays out, likely in the North. Home and belonging remain crucial themes in her arc, and the memories of Winterfell and her family strongly resonate throughout the sample chapter. The Sansa we witness in this chapter is on the cusp – of womanhood, power, and reclaiming her true identity.

Points of Foreshadowing/Curious details/Questions for further analysis:

- “They’re from the Sisters. Did you ever know a Sisterman who could joust?” – Well, as a matter of fact, Myranda, she just might have. If there’s anyone who deserves the title of “sisterman” it’s Sandor Clegane, who has been connected to both Sansa and Arya as a protector figure.

- Harry the Heir, Alayne thought. My husband-to-be, if he will have me. A sudden terror filled her. She wondered if her face was red. Don’t stare at him, she reminded herself, don’t stare, don’t gape, don’t gawk. Look away. Her hair must be a frightful mess after all that running. It took all her will to stop herself from trying to tuck the loose strands back into place. Never mind your stupid hair. Your hair doesn’t matter. It’s him that matters. Him, and the Waynwoods. – Trying to stop worrying about her “stupid hair” and thinking that it doesn’t matter seems like another blaring signal that actually it does, and this supports what LF will later tell her in the vaults about the fire shining in her hair.

- What is Sansa wearing in this chapter? For someone who usually loves to describe what Sansa is wearing, Martin is silent on the matter. Even at the feast when Sansa is the centre of attention, we get no description. Clothing symbolism is an important element in analysing Sansa’s chapters, so this is a curiously missing detail.

- Why is SR so calm at the feast? Alayne notes that he would have been given a strong dose of sweetmilk beforehand, but even she is still worried that the aggravation of seeing her with Harry might cause him to have a seizure. Furthermore, we saw SR wiping his nose when Sansa is with him earlier in the day. This may be a bad sign that the young lord is already dangerously overdosed, as the maester had previously expressed concerns in AFFC about whether he was bleeding from the nose.

- Food symbolism that still needs to be analysed: suckling pigs and pike.

- Ser Artys Arryn – conflated as the Winged Knight of legend — is said to have defeated the Griffin King. Jon Connington is the Lord of Griffin’s Roost and Hand of the King. Is the premise of the Winged Knight tourney itself a foreshadowing of the Vale not allying with Aegon?

(This essay is indebted to the great discussions that took place in the Pawn to Player thread at Westeros.org when the sample chapter was released two years ago.)